Book review: The World's Most Beautiful Thangka

Cosmology, view of life and death, and ethics in thangka and Tibetan Buddhism

"Quantum mechanics enables us to recognize that the universe is not a collection of objects, but a complex network of relationships among the parts of a unified whole. But this is precisely the way the world is experienced in Eastern mysticism. The language used by atomic physicists is strikingly similar to the descriptions of their experiences by the mystics." — The Tao of Physics, Fritjof Capra

Dear readers welcome back to another post of the "Amber Sealed" newsletter, where I explore artistic and creative works with timeless elegance and ideas that inspire me personally.

Are you surprised by the words above from the author and physicist Capra, and do you wonder how he drew the analogy between quantum mechanics and Eastern mysticism? The quote is from a book I recently delved into, focusing on thangkas. In it, the author mentions, “These words by the renowned Western physicist Capra invite readers to reassess religion, especially Buddhism,“ highlighting an intriguing cross-cultural dialogue on spirituality and science.

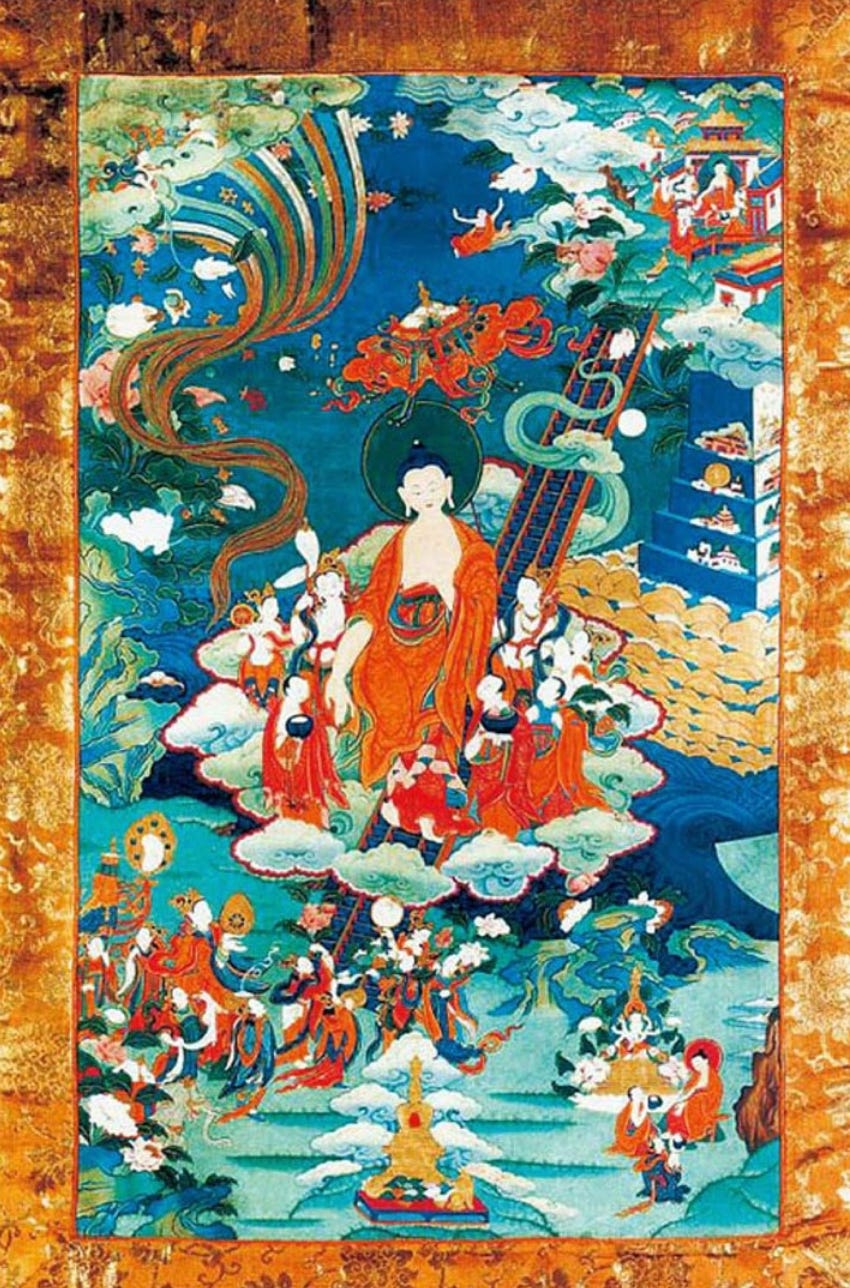

Thangka is a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton or silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala. The thangka drawing has long been revered as a legacy art in Tibetan Buddhism. For those without additional context, the exotic colors and delicate geometries in thangka paintings often imbue them with a layer of mysticism.

I especially love the Thangka painting of the mandala, which in Sanskrit simply means "circle." It is a geometric configuration of symbols, often used as a spiritual guidance tool for establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation and trance induction. Mandalas were introduced and made famous to modern Western thought by psychologist Carl Jung, who claimed that the urge to make mandalas emerges during moments of intense personal growth. In his autobiography, Jung wrote:

I sketched every morning in a notebook a small circular drawing, [...] which seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time. [...] Only gradually did I discover what the mandala really is: [...] the Self, the wholeness of the personality, which if all goes well is harmonious.

— Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, pp. 195–196. Wiki

In today's post, I want to present something different and provide a book review of "The World's Most Beautiful Thangka—The 'Three Realms' in Thangka," a book I recently read. This book delves into the profound spiritual and cultural dimensions of Tibetan Buddhism through the intricate art of thangka paintings, which encapsulate both Tibetan customs and the profound wisdom of the Buddha.

I want to share with you some of the key perspectives from the book that struck me the most, reflecting core cosmological concepts in Buddhism, many of which bear striking similarities to modern science and physics. Understanding these fundamental worldviews will serve as a valuable tool for us to delve beyond the beautiful colors and intricate geometries of thangka paintings and truly appreciate the spiritual depth underlying them.

So the next time you encounter a thangka painting, perhaps you'll perceive something beyond its colors and artwork (which are already amazing, of course!).

A brief historical background of thangka

Historical thangkas date back to the 13th/14th century, with some of the earliest specimens showing Amitabha surrounded by bodhisattvas, and the "Mandala of Vishnu" from 1420 A.D. being notable examples. The creation of a thangka involves precise geometric composition and symbolic elements, requiring the artist to have deep religious knowledge and artistic skill.

Thangkas are part of a rich history of Buddhist art, reflecting influences and historical interactions among Indian, Nepalese, and Chinese artistic traditions. Traditionally, thangkas are unframed and rolled up when not displayed, requiring careful preservation due to their delicate materials. They vary in size, with some large enough to be displayed on monastery walls during festivals, while others are intended for personal meditation.

Initially, creating Thangka paintings was a spiritual practice for gaining merit; however, it has evolved into a commercial activity, providing employment opportunities in the northern Himalayan regions, although Tibetans traditionally frown upon selling religious artifacts.

In a world where commercialization and mass production are becoming increasingly popular, people increasingly seek original, exotic, and delicately handcrafted art forms like thangka as symbols of good taste and wealth. Thangkas can sell for a few hundred to thousands of dollars on eBay, depending on their size and age, and the most expensive ones have been sold for millions of dollars at auction.

Nevertheless, it's crucial to explore the cultural and spiritual significance of these artworks rather than just seeing them as valuable items. Buying art solely for its collectible status without understanding its spiritual purpose, especially with thangka, which is meant to aid meditation and spiritual growth, is superficial.

So let's dive in!

Book review: The World's Most Beautiful Thangka

I am not a Buddhist devotee myself, so the symbols and messages behind thangka deities, scenes, and mandalas used to elude me. Fortunately, this month I came across a booklet titled "The World's Most Beautiful Thangka—The 'Three Realms' in Thangka," which explores famous thangka paintings in history and explains important concepts and beliefs in Buddhism along the way, including Buddhism's views on life and death, cosmology, ethics, and many other significant philosophical topics.

Unlike Han Buddhism (mainly in mainland China), Tibetan Buddhism carries a unique mystique, deeply rooted in the high plateaus of Tibet. Thangkas, beyond their vibrant beauty, offer insights into the Buddhist view of the universe, divided into the sacred and the mundane world called "Three Realms": Desire, Form, and Formless. The book emphasizes the importance of understanding these realms to appreciate human life's potential for enlightenment and freedom from the cycle of rebirth. Thus, thangkas are framed not merely as art, but as philosophical maps for overcoming life's challenges and finding true happiness.

The book vividly reveals a mysterious world that is rarely seen by the secular world, through 100 treasured thangkas from collections both in China and abroad. The book is written in Chinese, but in my newsletter, I will select five thangkas and share with you their significance and messages, offering a glimpse into Tibetan Buddhism's cosmology. However, the depth of thangka and Tibetan Buddhism far exceeds what can be conveyed in a brief newsletter. Therefore, I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in exploring further.

Also, I am definitely not an expert in thangka or Tibetan culture, so any criticism or corrections in the comments section are highly welcome, should I have mistranslated or misunderstood anything. Much appreciated!

The cosmology in thangka: A very macroscopic worldview

The worldview in Buddhism is a very macroscopic one. At the center of the world is Mount Meru, a mythical five-peaked mountain, surrounded by other significant mountains and oceans, home to the Trāyastriṃśa heaven, around which the sun and moon revolve.

This Thangka depicts the living environments of all sentient beings from the perspective of the Buddha. The top half of the thangka painting below is Mount Meru (the inverted triangle-like object). The concentric semicircular circles in the lower half represent the various hells in Buddhism, with red symbolizing extreme heat and blue symbolizing extreme cold.

Beyond heaven and hell, there are yet many revered Buddhist deities waiting to lead away those fortunate individuals who have attained enlightenment.

The Mount Meru in the Thangka, constructed of four-colored gems, towers high, with the Buddhas of the Five Directions seated at the summit of Mount Meru. Surrounding Mount Meru, there are living environments with life, including our Earth (Jambudvīpa), Purvavideha to the east, Aparagodaniya to the west, and Uttarakuru to the north. The Earth (where we live) is located to the south of Mount Meru, and because the southern face of Mount Meru is made of lapis lazuli gems, the sky above our Earth is reflected with a brilliant azure color by the lapis lazuli gems. — Chapter 1.1: The worldview of Buddha

There are three mainstream cosmological views of the universe in Buddhism, which I won't go into detail about. However, all three cosmological views share one important similarity:

From the perspective of Buddhism's core philosophy, Buddhism does not focus on revealing the origin of the universe or specific knowledge about the size and scope of the universe. This is because understanding these aspects does not significantly help in resolving the ultimate meaning of life and may even lead to confusion for people. — Chapter 1.2: The basic composition of the "Three Realms"

What fascinates me the most, is that cosmology in thangka shows a very similar view of how modern science views "time" in our universe.

The reason celestial bodies like the sun and the moon can remain suspended in the sky is due to the force of their fixed orbits, according to the "Kalachakra Tantra." This is very close to modern scientific understanding. In the Kalachakra teachings by Tsering Rinpoche, it is mentioned that Tibetan astronomy primarily uses Kalachakra astronomy. Its calculations of planetary orbits, and the annual solar and lunar eclipses, are very close to those calculated by modern scientific observatories. The precision is almost as accurate as that of observatory electronic computers, though the terminologies used are different. — Chapter 1.2: The basic composition of the "Three Realms"

These thangkas are often used as tools for visualization and spiritual progress by Buddhists. Additionally, many document the early wisdom of Tibetan Buddhism's observations of the universe. Understanding the macroscopic worldview in Buddhism is the first step towards appreciating the map-like scenes in thangka paintings that depict the universe.

Buddism's view of life and death

In Buddhism, the world all the beings live in is called the "three realms", which is the world of desire (populated by hell beings, hungry ghosts, animals, and us humans and lower demi-gods), the world of form (populated by dhyāna-dwelling gods), and the world of formlessness, a noncorporeal realm populated with four heavens.

The "three realms" are further divided into "the six paths", six worlds where all beings will forever repeat the cycles of death and reincarnation based on their karma. The six paths are:

the world of gods or celestial beings (deva) ;

the world of warlike demigods (asura) ;

the world of human beings (manushya) ;

the world of animals (tiryagyoni) ;

the world of hungry ghosts (preta) ;

the world of Hell (naraka).

The worlds of gods, warlike demigods, and human beings are considered the “three virtuous destinies” because they experience more pleasure and less pain, especially in the world of gods, for instance. The latter three paths are regarded as the “three evil destinies”.

That is to say, in Buddhism, aspiring to "heaven" or the world of celestial beings is not seen as the ultimate goal. Buddhism posits that all life undergoes a cyclical process of death and rebirth within the 'six paths.' Going to the world of gods, although it may offer more pleasure and less pain, is still considered a transient pleasure and not ultimate enlightenment. Buddhists pursue spiritual practices to transcend the cycle of the six paths and ultimately achieve enlightenment, or Nirvana.

Understanding this perspective on life and death is crucial to appreciating thangka paintings that depict the Wheel of Samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth), which are quite common in Tibetan Buddhism.

This thangka depicts the cycle of life in the “three realms“ and “six paths”.

In the Thangka, the one tightly grasping the Wheel of Samsara is Yama, the lord of death, signifying that no beings of the six realms can escape the suffering of samsara.

Above the Wheel of Samsara, there are three virtuous paths: in the center is the realm of gods, with the realm of Asuras (demi-gods) and the realm of humans on the left and right sides, respectively. Below are three evil paths: in the center is the realm of hell, with the realms of animals and hungry ghosts on the left and right sides. The outermost circle consists of twelve sections representing the Twelve Links of Dependent Origination. Above the Thangka, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas are depicted, indicating that they are watching over the beings in the six realms, guiding those with affinity to escape the sea of suffering.

The center of the entire image represents the “three poisons”: the pigeon (symbolizing greed), the snake (symbolizing anger), and the pig (symbolizing ignorance), illustrating how these three negative states of mind are intertwined and are the root of all suffering.

The fierce-looking Yama, the lord of death, is also a symbol of the time that governs our universe.

In the Wheel of Samsara of the three realms and six paths, the fierce-looking Yama represents the symbol of time. He is impartial and unyielding, showing no favoritism. All sentient beings that are continuously reborn in the three realms due to ignorance, afflictions, and karma are under his control and swallowing. Therefore, in the Buddhist Tantric tradition of the Kalachakra Tantra, life and the universe are interpreted based on time. — Chapter 1.2: The basic composition of the "Three Realms"

How fascinating!

Karma and causality

It's important to note that "causality" is a key component to understanding Buddhism's cosmology. Buddism believes that all the differences in the world are not created by deities, but are the manifestations of the collective karma of all beings:

People often say that life is in movement. However, from the Buddhist perspective, aside from movement itself, there is nothing that can be called life. Life is merely a label and a collective term for a series of movements of various cause-and-effect relationships. Although this concept of denying the self and soul is difficult to understand, it is extremely important. It is the sharp blade that cuts through the chains of samsara, the arrow of wisdom targeting ignorant notions, and the supreme treasure for liberation from the cycle of rebirth. — Chapter 2.3: The death of sentient beings in the three realms

Buddism therefore denies the existence of any messiah-like deity to save all sentient beings from suffering. All is the consequence of the cause:

The Buddha once said that one is one's own savior, and there is no savior besides oneself. He also stated that he cannot remove the suffering of sentient beings with his hands, nor can he wash away their sins with water, nor can he transplant his enlightenment to others. He can only point out the path to enlightenment to sentient beings. — Charpter 4.1: Karma

This is a very important concept to understand to be able to comprehend some of the deity figures in the Thangka paintings. For instance, the thangka below paints Vipāka, which symbolizes the result of sentient beings being reborn in the six paths due to the power of their virtuous and non-virtuous actions.

How fascinating! It seems to me that there is a light of reason within Buddhism. In fact, all arguments rely on logical reasoning, not on blindly believing in Buddha's teachings. This characteristic is a hallmark of Buddhism, which also applies to justifying the doctrine of reincarnation. (The book briefly explains how this logical reasoning is conducted, which I won't detail in the newsletter.)

The ethics

The karma and causality stand core to all the doctrines of Buddhism. Ethics and disciplines are highly emphasized, as it's the only way to improve one's living environment as well as achieve ultimate enlightenment. Happiness and paths towards enlightenment come with doing good deeds, and vice versa.

However, importantly, there is no concept of reward or punishment in Buddhism, as explained by the author of the book:

Attaining happiness is not a reward for doing good deeds, nor is experiencing suffering a punishment for doing bad deeds — the result of karma is not reward or punishment; it is simply a consequence.

In Buddhism, the "Ten Evil Deeds" and the "Ten Virtuous Deeds" are moral guidelines that outline actions considered harmful or beneficial for spiritual progress.

The Ten Evil Deeds are: Killing (including suicide), stealing, sexual misconduct, lying or false speech, divisive speech, harsh speech, idle chatter or gossip, covetousness or greed, ill will or hatred, wrong views or distorted perspectives (mainly referring to disbelief in the cycle of rebirth within the six paths). The Ten Virtuous Deeds are effectively the opposite of these (abstaining from killing, abstaining from stealing, and so on).

One interesting detail that caught my attention is the 7th evil deed "idle chatter or gossip", which refers to "all the meaningless chatters" in Buddhism and that includes gossip, international politics, and various exclamations and drunken talk.

Why would politics be considered a "meaningless chatter"? Let me know your thoughts. Nevertheless, many of us do waste valuable time in life through "idle chatter or gossip". What a reminder!

Understanding the fundamental ethics and doctrines of Buddhism is essential for appreciating the intricate details of various deity figures depicted in thangkas. Many of these deities represent specific virtues or vices. Thangkas are actually used as tools for meditation and spiritual progress.

For example, in the upper right corner of this thangka, we see the Ratnacandra Tathagata, portrayed with a white body and hands forming the teaching mudra. Among the ten evil deeds prohibited in Buddhism, killing is regarded as the most severe form of bodily misconduct. Those who pay homage and recite the name of the Ratnacandra Tathagata can purify themselves of the five gravest transgressions: patricide, matricide, killing an Arhat, sowing discord among the Sangha, and causing the Buddha's body to bleed.

Closing remarks

Of course, this newsletter isn't about teaching you everything there is to know about Tibetan Buddhism. I'm just pulling out some key parts from a book to give you a taste of what's inside. If you're curious and want to dive deeper into thangkas and Buddhism, definitely check out the book for the full context.

Reading this has opened my eyes to a new way of seeing thangka art. Before, it was just beautiful and colorful to me, but now I see it's much more than that.

Coming from a scientific background, I have encountered several fascinating concepts, such as the light of reason inherent in the Buddhist religion, and how its cosmology, perception of time, and the principle of causality (or karma) bear remarkable resemblances to modern scientific theories.

And there's something comforting about the idea that there's more to life than just us. This transcendent entity is not necessarily a deity or a creator dictating the workings of the universe. To different individuals, it may mean different faiths. Yet, the mere act of humbling oneself and acknowledging the existence of an "ultimate enlightenment" provides a profound and lasting solace amid the trivial pursuits of daily life, at least in my personal experience.

In some schools of Buddhism, the briefest moment of thought is known as a "Ksana," which is incredibly fleeting. Various scriptures offer metaphors to describe its duration, such as the time it takes for a very strong adult to snap their fingers, equating to sixty-five Ksanas. Regardless of the metaphor, the concept is meant to illustrate the notion of a thought that cannot be any more transient.

To me, the concept of the Ksana is fascinating. One Ksana can embody nothingness, yet it can also expand to encompass the vastness of an entire universe, the three realms, and the six paths. What unfolds before us exists within the Ksana of our thoughts. Reading this book has served as a powerful reminder of the significance of our actions and words, emphasizing the responsibility we carry in the fleeting yet profoundly meaningful moments of our lives.

If you like my content, please consider buying me a coffee so I can get a better camera and take some legit photography lessons so pictures in my newsletter can look nicer. Much appreciated ❤️.

I would also appreciate it if you could share this post with others who you think would resonate with or find the content helpful. Thank you!

Quick announcement: Amber’s side project “Amber Sealed”!

I recently launched my side project, an online boutique called "Amber Sealed," which curates a personal selection of handmade and traditional craftsmanship from some of the most inventive communities in China. I enjoy talking with independent artists, designers, and craftsmen and hearing their stories and inspirations behind their creations. Motivated by these interactions, I envisioned an online platform that would bring these artisanal treasures, each combining traditional craftsmanship with modern aesthetics, to a wider audience.

None of the items in my store are mass-produced or can be bought through Amazon or Temu. Human efforts and intentions matter more than ever in the age of AI and automation. We are empowering artisans and preserving ancient crafts with every purchase.

I'd love to hear your thoughts on my idea to hunt for non-mass-produced, handmade, and artisan pieces with lasting beauty :) I currently ship to North America, Australia, Singapore, and Hong Kong. You are also welcome to follow my Instagram, where I post pictures and reels to spotlight creative things if you prefer visual content.

Store link: https://www.ambersealed.com/

Other Reads

Art Brut: once we all had that inner child with us

When was the last time you felt urged to write, draw, or create something spontaneously, without any rules or specific purposes? Have you ever felt that it's incredibly difficult to draw or write WHATEVER you like as you grow up? Recently, I encountered some truly amazing paintings that deeply touched me and helped me reconnect with the sense of lost "sp…

How chance composes life's soundscape

I recently came to appreciate a solo piano piece called "Music of Changes" composed by American composer John Cage in 1951. "Music of Changes" is a groundbreaking piece in music history. During the composition process, Cage consulted the I Ching, an ancient Chinese book commonly known as a divination system in Chinese culture (though it isn't actually a…