How chance composes life's soundscape

Some cultural context on I Ching and how it inspired John Cage’s “Changes of Music”

I recently came to appreciate a solo piano piece called "Music of Changes" composed by American composer John Cage in 1951. "Music of Changes" is a groundbreaking piece in music history. During the composition process, Cage consulted the I Ching, an ancient Chinese book commonly known as a divination system in Chinese culture (though it isn't actually a divination text, as I'll explain later), to make compositional decisions such as notes, rhythms, dynamics, and structures.

Let’s get a quick sense of what it sounds like:

I first came across the piece while studying music history in college nearly 10 years ago. At the time, I hated the piece, despite the mystical quality behind Cage's innovative compositional idea — it sounded like random strikes on a digital board, and I had to pull an all-nighter writing an essay about it. (That essay earned me a C+, and I never thought I would come to appreciate the music as well as the composer, if ever.)

10 years later, I somehow began to appreciate the composition as I rediscovered the essence of I Ching. I want to walk you through the context behind Cage's composition, how he drew inspiration from the I Ching, and how I came to rediscover the philosophical depth behind it. Known as the "Book of Changes" in English, this ancient Chinese classic is crucial for understanding Cage's compositional idea.

First, a very brief context on who John Cage is and how “Music of Changes” was composed. For musicians, John Cage should be a hallmark name and one of the most influential avant-garde composers in the 20th century. For the general public, however, his music styles may seem obscure. He's known for the non-standard use of musical instruments (let's just say for instance, he put many weird items into the piano strings to produce non-standard sounds, forks, screws, pennies, woolen materials, you name it). One of his most famous works could be the 4’33’’, a three-movement performance where the score instructs performers NOT TO PLAY their instruments during the entire duration of the piece throughout the three movements.

So it would not surprise us too much that an avant-garde like Cage would venture into something that’s completely unbounded by the musical tradition.

Cage’s "Music of Changes" - music composed by applying I Ching

Let's first examine Cage's creative process to understand how this piece of music maintains its unique position in contemporary music.

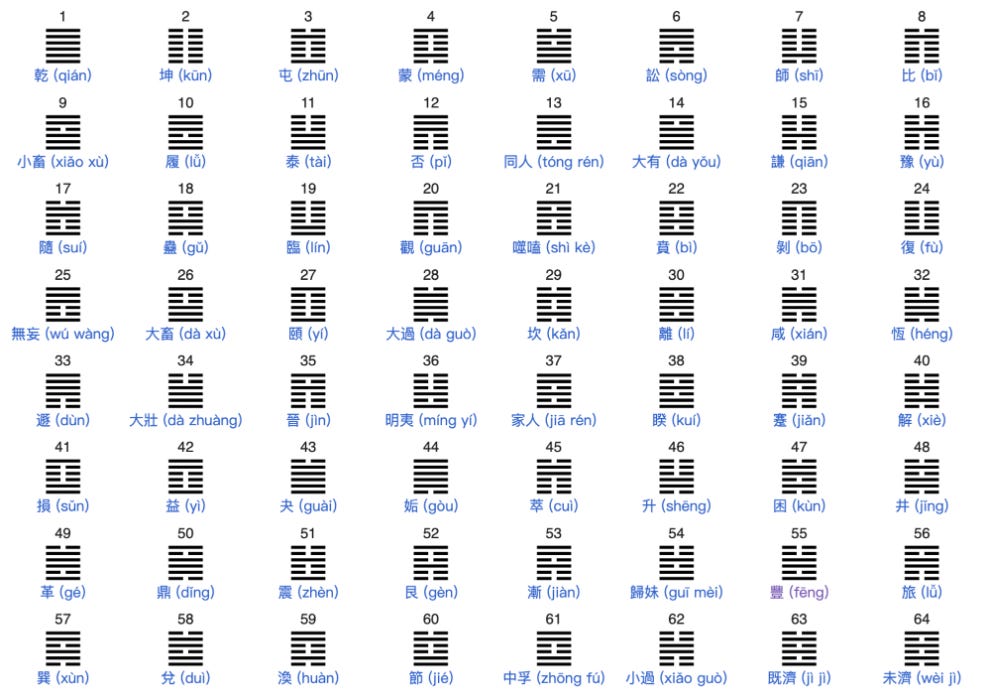

The I Ching uses a system of 64 hexagrams (unique combinations of six lines that are either broken or unbroken) to guide users through the decision-making process. In ancient Chinese practice, fortune tellers would toss three coins to randomly generate a number sequence. This sequence is then deterministically mapped to one of the 64 hexagrams, each carrying a specific message or prediction. (Each hexagram is accompanied by corresponding statements, which are used to interpret the divination results.)

*I'm not writing about how you do the practice, so I'm going to skip the details. And I think that's pseudoscience (btw let's revisit that concept later in the newsletter). However, interested readers, you can actually buy an I Ching divination kit on Amazon.

Cage used a modified version of the I Ching hexagram system. He created an 8x8 sound event chart to mirror the I Ching's 64 hexagrams. To compose a music segment, the I Ching is first consulted to determine which sound event (think of them as note sequences for simplicity) should be selected from his chart, which contains different music events, including silences. (In fact, in Cage's sound charts, 32 out of 64 fields are silences; he indeed loved silence!) The same procedure is then applied to choose durations, dynamics, etc.

The actual composition process is more complex than what I've described. However, for simplicity purpose, just imagine that Cage tossed coins to select what musical material should be used from a magic-square like chart — essentially, Cage abandoned the idea that the composer has total control over how the music would develop, and let chance events shape the music.

The piece marks a pivotal work in music history, as it questions the very nature of music and the composition. But I won’t divert into another music history lesson today. Instead, I want to focus on one most important lesson that I myself have just recently came to appreciate. This is what I make of Cage’s “Music of Changes”: the philosophical depth behind the process of the composition itself is more important than hearing the composed music itself over and over again.

And that's also the essence of I Ching — it's not a divination text dictating what our life's ending would look like, but rather a self-reflection tool to understand how our destiny passes through the everlasting changes.

A crash course on I-Ching’s hexagram system

To better understand the philosophical depth, I want to do my best to give you a crash course on the origin of the I Ching's hexagram system. It takes years of scholarly research to completely capture the philosophical depth of this classic, so I'm really just providing a very simplified version to illustrate the essence. (The explanation is adapted from the lecture series by Professor Zeng Shiqiang, who is a renowned Chinese sinologist and scholar, best known for his work on I Ching and contributions to the Chinese style of management.)

I-Ching’s 64 hexagram may seem completely obscure upon the first glance. But in fact, it's the earliest wisdom in Chinese culture, observing natural phenomena to deduce governing laws, all summarized in a chart.

Let's use a simple example to illustrate how the first hexagram 乾 qián, which loosely translates to "heaven," is constructed:

As previously mentioned, the I Ching's hexagram is composed of six lines, which are either broken or unbroken. What do these broken and unbroken lines signify? They were derived from direct observations of nature.

The unbroken line symbolizes the sky, reflecting the continuous and unbroken cosmos. This symbolizes the masculine energy of Yang, as the sky stands still and supports the vast dome under which we live. The broken line represents the earth, segmented by lakes and valleys. This signifies the feminine energy of Yin, as the Earth nurtures life despite the weathering.

From the binary line element, more complex "trigrams" can be constructed. Let's take the trigram of the "water" element as an example: the forever flowing energy (the unbroken line) that goes through the earth (broken lines) — that's water.

The "hexagram" is then constructed from stacking two trigrams. The first of the 64 hexagrams, 乾 qián, is essentially the doubling of two trigrams with all unbroken lines symbolizing the sky. You may be able to guess — this hexagram's name, "heaven," symbolizes the utmost force of masculine energy.

Why is this important to know how the hexagrams are constructed?

The I-Ching has long been associated with divination or fortune-telling tools. The origin of the hexagram, although obscure, comes from the mythological culture hero Fu Xi, a snake-tailed, human-faced figure. (His sister and wife, Nvwa, is believed to have created human beings.) In mythology, the trigram was created by Fu Xi after studying the patterns of nature in the sky and on the earth. He deduced that the universe could be reduced to the yin and yang duality and created eight trigrams. Each reflects a basic natural component that governs the operation of the universe: heaven, lake, fire, thunder, wind, water, mountain, and earth.

So you can see from here — The trigrams weren't invented for use as a divination text, but rather a high-level summary of the observations and laws of the universe.

It wasn't until Emperor Wen (1099–1050 BC) of the Zhou Dynasty turned the trigrams into 64 hexagrams and wrote brief oracles for each of them, adding a layer of mystery to the whole root of the hexagram system. (For context, the Zhou Dynasty’s royal family monopolized the right to interpret divination result, using it as a tool to govern the country. This gives an idea of how it gradually became associated solely as a divination manual.) It later evolved into a cosmological text with philosophical commentaries. These commentaries, known as the “Ten Wings”, were added later and provide philosophical depth and moral interpretation.

The “meaningful coincidences”

So two types of lines, representing yin and yang, compose the trigram. Each trigram is made up of three lines, resulting in eight possible combinations. Eight unique trigrams then form a hexagram by stacking one trigram above another, creating a stack of six lines. This results in 8 x 8 = 64 possible hexagram combinations.

Does this sound familiar? If the idea reminds you of basic concepts such as linear algebra or binary in computer science, you're not alone in that thought. Indeed, the hexagram system in the I Ching coincides with many concepts that have become central to modern science in both the eastern and western worlds.

Perhaps the most influential example that sparked intellectual discourse was Leibniz's commentaries on I Ching. In 1703, he argued that the hexagram system proved the universality of binary numbers and theism, since the broken lines, the "0" or "nothingness", cannot become solid lines, the "1" or "oneness", without the intervention of God (Wiki). The argument was criticized by Hegel, but let's not dive into another philosophical discourse just yet.

In Leibniz's quest for the Characteristica universalis, a universal and formal language envisioned by Leibniz to express mathematical, scientific, and metaphysical concepts, Leibniz discovered a link between binary digits and concepts in I Ching.

Apart from Boolean logic, I Ching also coincides with many other concepts. For instance, many say the 64 hexagram coding system coincides with the 64 genetic code system (which are also constructed from the system of triples). These coincidences add layers of enigma to the I Ching text, as it somehow encodes the myths and undiscovered truths that mysteriously govern our lives, prompting people to think of I Ching as a definitive prediction of destiny.

Carl Jung developed a deep interest in the I Ching, exploring his concept of synchronicity — "circumstances that appear meaningfully related yet lack a causal connection". Jung practiced the I Ching oracle for over 30 years, even incorporating it into his psychotherapy. However, he did not view the divination text as a definitive prediction (we know that’s pseudoscience and superstition), but rather used it as a tool to bridge the inner (psyche) and outer worlds (matter), in Jung's own words:

A certain curious principle that I have termed synchronicity, a concept that formulates a point of view diametrically opposed to that of causality. Since the latter is a merely statistical truth and not absolute, it is a sort of working hypothesis of how events evolve one out of another, whereas synchronicity takes the coincidence of events in space and time as meaning something more than mere chance.

The Chinese mind, as I see it at work in the I Ching, seems to be exclusively preoccupied with the chance aspect of events. What we call coincidence seems to be the chief concern of this peculiar mind, and what we worship as causality passes almost unnoticed.

Jung captured the exact essence of the I Ching — “the acceptance of chance, rather than a life dictated by the oracle”. What does this mean? Essentially, the I Ching does not operate as a casual oracle that states “if you do A, then B will definitely happen in your life”. Instead, it suggests that “random events can occur in your life, yet still create meaningful impacts”. So, rather than using an oracle to “secure” your destiny, Jung delved into synchronistic moments to understand how they unfold personally for each individual, thereby providing therapeutic value.

How does "chance" lead to "meaning"?

Let's quickly revisit Hegel’s criticism.

When Leibniz believed that he had found a pathway towards universality, Hegel criticized that the "binary system and Chinese characters were 'empty forms' that could not articulate spoken words with the clarity of the Western alphabet."

The critique holds some merit. In actuality, the interpretation of the I Ching divination result is vague, with no definitive right or wrong, reflecting one's own expectations.

If one wishes to get a sense of how vague the interpretation can be, let’s just look at how I Ching was translated into other languages. The translation of I Ching into English mirrors the inherent ambiguity of the hexagram system. Scholars' translation styles vary—Hinton offers a poetic rendition, Minford takes a minimalist approach, while others like Richard John Lynn seek definitive interpretations. (For those interested in delving deeper, here's a fascinating article by Eliot Weinberger on how I Ching's English translations changed over time.)

For now, let's examine one example explained in Weinberger’s article:

…the differences among all translations—is apparent if we look at a single hexagram: number 52, called Gen.

Minford translates the name as “Mountain” for the hexagram is composed of the two Mountain trigrams, one on top of the other. His translation of the text throughout the book is minimalist, almost telegraphese, with each line centered, rather than flush left.

Hinton calls the hexagram “Stillness” and translates into prose: “Stillness in your back. Expect nothing from your life. Wander the courtyard where you see no one. How could you ever go astray?”

Wilhelm has “Keeping Still, Mountain” as the name of the hexagram.

The Columbia University Press I Ching, translated by Richard John Lynn and billed as the “definitive version” “after decades of inaccurate translations,” has “Restraint” for Gen: “Restraint takes place with the back, so one does not obtain [sic] the other person. He goes into that one’s courtyard but does not see him there. There is no blame.” Lynn’s odd explanation, based on the Han dynasty commentator Wang Bi, is that if two people have their backs turned, “even though they are close, they do not see each other.” Therefore neither restrains the other and each exercises self-restraint.

*Quoting Weinberger's writing; paragraph abbreviated.

See how the translation of a single hexagram can differ, even though each hexagram already has some oracle text to illustrate its meaning?

Interpreting the message in the divination process isn't much different from translating the oracle's statement into another language.

If you consult the I Ching about whether you should proceed with a certain action and receive an inauspicious hexagram, should you still move forward? According to the I Ching, if you genuinely want to pursue it, you should, as an inauspicious result does not guarantee failure. It merely serves as a reminder to minimize potential losses by carefully planning strategies. Conversely, if I Ching predicts auspicious outcomes, it doesn't guarantee success. Rather, it's intended to boost morale and remind you to stay humble. Success could just be an "auspicious coincidence" bestowed upon your life.

As Weinberger wrote in the article, James Legge, who “produced the first somewhat reliable English translation of I Ching in 1882”, argued:

Since Chinese characters were not, he claimed, “representations of words, but symbols of ideas,” therefore “the combination of them in composition is not a representation of what the writer would say, but of what he thinks.”

The difficulty in translating the oracle text in I Ching precisely reflects its core — the ambiguity. It's a guide (not a definitive oracle) to living an ethical and meaningful life, a tool to understand wisdom and ideas, and to accept our destiny (which are also "meaningful coincidences") amid the dynamics of an ever-changing world. (The "I" in I Ching, which is a phonetic translation of the original Chinese 易 Yi, stands exactly for the meaning of "changing").

Let's say I had a rough day and sat down to toss the coins and consult the I Ching, and I got the first hexagram, "heaven". The statement reads:

“天行健,君子以自强不息”

What does this translate to? A variety of possible solutions exist. Interpretations even differ among Chinese scholars. To get a sense, let's just consider the version by Richard Wilhelm, a German sinologist whose translation of the I Ching is widely recognized for its quality.

The movement of heaven is full of power. Thus the superior man makes himself strong and untiring.

Does this mean I will be invincible and full of power? The I Ching doesn't guarantee a particular outcome. Instead, it suggests that the future depends on a prerequisite: one must strive to be as strong and untiring as the heaven.

Indeed, hexagrams are "empty forms"; they do not dictate anyone's destiny. They provide no definitive right or wrong, but rather foster self-reflection. They help to organize thoughts, reflect on our relationship with space and time, and understand ourselves better — it’s tool to understand our fears, expectations, desires, wishes, and mental traps, allowing us to view ourselves from a third-person perspective.

Rediscovering my appreciation for Cage's "Music of Changes"

I loved physics as a student. I believed it helped me find rational explanations for what happened in my life—that's of therapeutic value to me personally.

However, 10 years later, I somehow rediscovered the true message of the I Ching, which helped me find a way to not just understand, but equally important, to deal with what happened to me.

Studying physics made me feel outward and rational, ambitiously striving to encompass all occurrences within some kind of clean model.

The I Ching, in contrast, is inward, subjective, and practical. Its oracle statements are concise, arguably too concise to convey any definitive meaning. This makes any divination practice using the I Ching a pseudoscience. However, its vagueness remains a practical tool for guiding self-discovery and an inward life.

So that brought me back to the starting point, the "Music of Changes" that I despised back in college. For me, the process of rediscovering appreciation was a fascinating one. I was born and raised in China until 17 but I knew basically nothing about I Ching except for its use as a divination text. So when I first heard about Cage's compositional process, I wasn't impressed as I thought, "oh this is just another contemporary composer trying out a gimmick to catch attention and has no real musicality."

The philosophical depth of the musical composition is indeed more important than repeatedly listening to the composed music itself. (I still don’t appreciate the musicality of the finished work tho. Let me know what you make of it. Is it still a good piece of music?)

Despite the use of chance events in the compositional process, Cage considered the "Music of Changes" a deterministic work. However, the concept of "chance" undeniably had a profound impact on Cage. This led him to pioneer the experiment of "Indeterminate music" later in his career. This composing approach leaves some aspects of a musical work open to chance or the interpreter's free choice, completely challenging our established concepts of music and composition. In Cage's own words on "indeterminate music":

"My intention is to let things be themselves.”

Cage wasn't adopting the divination aspect of the I Ching, but rather its core essence — acknowledging chance in life and be with it.

If you like my content, please consider buying me a coffee so I can get a better camera and take some legit photography lessons so pictures in my newsletter can look nicer. Much appreciated ❤️.

Instagram: @amberrrrrrrrrrrrz

我竟然看到这样一篇独特视角的文章,很棒!